People are responsive creatures; hold freshly baked bread before us, and our mouths water; a sudden clap of thunder makes us jump; these “irritants” and many others are the stimuli that continually greet us and are interpreted by our nervous system; the four “traditional” senses—smell, taste, sight, and hearing- are called special senses.

Functions of Special Senses

The functions of the five special senses include:

- Vision. Sight or vision is the capability of the eye(s) to focus and detect images of visible light on photoreceptors in the retina of each eye that generates electrical nerve impulses for varying colors, hues, and brightness.

- Hearing. Hearing or audition is the sense of sound perception.

- Taste. Taste refers to the capability to detect the taste of substances such as food, certain minerals, and poisons, etc.

- Smell. Smell or olfaction is the other “chemical” sense; odor molecules possess a variety of features and, thus, excite specific receptors more or less strongly; this combination of excitatory signals from different receptors makes up what we perceive as the molecule’s smell.

- Touch. Touch or somatosensory, also called tactition or mechanoreception, is a perception resulting from activation of neural receptors, generally in the skin including hairfollicles, but also in the tongue, throat, and mucosa.

The Eye and Vision

Vision is the sense that has been studied most; of all the sensory receptors in the body 70% are in the eyes.

Anatomy of the Eye

Vision is the sense that requires the most “learning”, and the eye appears to delight in being fooled; the old expression “You see what you expect to see” is often very true.

External and Accessory Structures

The accessory structures of the eye include the extrinsic eye muscles, eyelids, conjunctiva, and lacrimal apparatus.

- Eyelids. Anteriorly, the eyes are protected by the eyelids, which meet at the medial and lateral corners of the eye, the medial and lateral commissure (canthus), respectively.

- Eyelashes. Projecting from the border of each eyelid are the eyelashes.

- Tarsal glands. Modified sebaceous glands associated with the eyelid edges are the tarsal glands; these glands produce an oily secretion that lubricates the eye; ciliary glands, modified sweat glands, lie between the eyelashes.

- Conjunctiva. A delicate membrane, the conjunctiva, lines the eyelids and covers part of the outer surface of the eyeball; it ends at the edge of the cornea by fusing with the corneal epithelium.

- Lacrimal apparatus. The lacrimal apparatus consists of the lacrimal gland and a number of ducts that drain the lacrimal secretions into the nasal cavity.

- Lacrimal glands. The lacrimal glands are located above the lateral end of each eye; they continually release a salt solution (tears) onto the anterior surface of the eyeball through several small ducts.

- Lacrimal canaliculi. The tears flush across the eyeball into the lacrimal canaliculimedially, then into the lacrimal sac, and finally into the nasolacrimal duct, which empties into the nasal cavity.

- Lysozyme. Lacrimal secretion also contains antibodies and lysozyme, an enzyme that destroys bacteria; thus, it cleanses and protects the eye surface as it moistens and lubricates it.

- Extrinsic eye muscle. Six extrinsic, or external, eye muscles are attached to the outer surface of the eye; these muscles produce gross eye movements and make it possible for the eyes to follow a moving object; these are the lateral rectus, medial rectus, superior rectus, inferior rectus, inferior oblique, and superior oblique.

Internal Structures: The Eyeball

The eye itself, commonly called the eyeball, is a hollow sphere; its wall is composed of three layers, and its interior is filled with fluids called humors that help to maintain its shape.

Layers Forming the Wall of the Eyeball

Now that we have covered the general anatomy of the eyeball, we are ready to get specific.

- Fibrous layer. The outermost layer, called the fibrous layer, consists of the protective sclera and the transparent cornea.

- Sclera. The sclera, thick, glistening, white connective tissue, is seen anteriorly as the “white of the eye”.

- Cornea. The central anterior portion of the fibrous layer is crystal clear; this “window” is the cornea through which light enters the eye.

- Vascular layer. The middle eyeball of the layer, the vascular layer, has three distinguishable regions: the choroid, the ciliary body, and the iris.

- Choroid. Most posterior is the choroid, a blood-rich nutritive tunic that contains a dark pigment; the pigment prevents light from scattering inside the eye.

- Ciliary body. Moving anteriorly, the choroid is modified to form two smooth musclestructures, the ciliary body, to which the lens is attached by a suspensory ligament called ciliary zonule, and then the iris.

- Pupil. The pigmented iris has a rounded opening, the pupil, through which light passes.

- Sensory layer. The innermost sensory layer of the eye is the delicate two-layeredretina, which extends anteriorly only to the ciliary body.

- Pigmented layer. The outer pigmented layer of the retina is composed pigmented cells that, like those of the choroid, absorb light and prevent light from scattering inside the eye.

- Neural layer. The transparent inner neural layer of the retina contains millions of receptor cells, the rods and cones, which are called photoreceptors because they respond to light.

- Two-neuron chain. Electrical signals pass from the photoreceptors via a two-neuron chain-bipolar cells and then ganglion cells– before leaving the retina via optic nerveas nerve impulses that are transmitted to the optic cortex; the result is vision.

- Optic disc. The photoreceptor cells are distributed over the entire retina, except where the optic nerve leaves the eyeball; this site is called the optic disc, or blind spot.

- Fovea centralis. Lateral to each blind spot is the fovea centralis, a tiny pit that contains only cones.

Lens

Light entering the eye is focused on the retina by the lens, a flexible biconvex, crystal-like structure.

- Chambers. The lens divides the eye into two segments or chambers; the anterior (aqueous) segment, anterior to the lens, contains a clear, watery fluid called aqueous humor; the posterior (vitreous) segment posterior to the lens, is filled with a gel-like substance called either vitreous humor, or the vitreous body.

- Vitreous humor. Vitreous humor helps prevent the eyeball from collapsing inward by reinforcing it internally.

- Aqueous humor. Aqueous humor is similar to bloodplasma and is continually secreted by a special of the choroid; it helps maintain intraocular pressure, or the pressure inside the eye.

- Canal of Schlemm. Aqueous humor is reabsorbed into the venous blood through the scleral venous sinus, or canal of Schlemm, which is located at the junction of the sclera and cornea.

Eye Reflexes

Both the external and internal eye muscles are necessary for proper eye function.

- Photopupillary reflex. When the eyes are suddenly exposed to bright light, the pupils immediately constrict; this is the photopupillary reflex; this protective reflex prevents excessively bright light from damaging the delicate photoreceptors.

- Accommodation pupillary reflex. The pupils also constrict reflexively when we view close objects; this accommodation pupillary reflex provides for more acute vision.

The Ear: Hearing and Balance

At first glance, the machinery for hearing and balance appears very crude.

Anatomy of the Ear

Anatomically, the ear is divided into three major areas: the external, or outer, ear; the middle ear, and the internal, or inner, ear.

External (Outer) Ear

The external, or outer, ear is composed of the auricle and the external acoustic meatus.

- Auricle. The auricle, or pinna, is what most people call the “ear”- the shell-shaped structure surrounding the auditory canal opening.

- External acoustic meatus. The external acoustic meatus is a short, narrow chamber carved into the temporal bone of the skull; in its skin-lined walls are the ceruminous glands, which secrete waxy, yellow cerumen or earwax, which provides a sticky trap for foreign bodies and repels insects.

- Tympanic membrane. Sound waves entering the auditory canal eventually hit the tympanic membrane, or eardrum, and cause it to vibrate; the canal ends at the ear drum, which separates the external from the middle ear.

Middle Ear

The middle ear, or tympanic cavity, is a small, air-filled, mucosa-lined cavity within thetemporal bone.

- Openings. The tympanic cavity is flanked laterally by the eardrum and medially by a bony wall with two openings, the oval window and the inferior, membrane-coveredround window.

- Pharyngotympanic tube. The pharyngotympanic tube runs obliquely downward to link the middle ear cavity with the throat, and the mucosae lining the two regions are continuous.

- Ossicles. The tympanic cavity is spanned by the three smallest bones in the body, the ossicles, which transmit the vibratory motion of the eardrum to the fluids of the inner ear; these bones, named for their shape, are the hammer, or malleus, the anvil, or incus, and the stirrup, or stapes.

Internal (Inner) Ear

The internal ear is a maze of bony chambers, called the bony, or osseous, labyrinth, located deep within the temporal bone behind the eye socket.

- Subdivisions. The three subdivisions of the bony labyrinth are the spiraling, pea-sized cochlea, the vestibule, and the semicircular canals.

- Perilymph. The bony labyrinth is filled with a plasma-like fluid called perilymph.

- Membranous labyrinth. Suspended in the perilymph is a membranous labyrinth, a system of membrane sacs that more or less follows the shape of the bony labyrinth.

- Endolymph. The membranous labyrinth itself contains a thicker fluid called endolymph.

Chemical Senses: Taste and Smell

The receptors for taste and olfaction are classified as chemoreceptors because they respond to chemicals in solution.

Olfactory Receptors and the Sense of Smell

Even though our sense of smell is far less acute than that of many other animals, the human nose is still no slouch in picking up small differences in odors.

- Olfactory receptors. The thousands of olfactory receptors, receptors for the sense of smell, occupy a postage stamp-sized area in the roof of each nasal cavity.

- Olfactory receptor cells. The olfactory receptor cells are neurons equipped witholfactory hairs, long cilia that protrude from the nasal epithelium and are continuously bathed by a layer of mucus secreted by underlying glands.

- Olfactory filaments. When the olfactory receptors located on the cilia are stimulated by chemicals dissolved in the mucus, they transmit impulses along the olfactory filaments, which are bundled axons of olfactory neurons that collectively make up the olfactory nerve.

- Olfactory nerve. The olfactory nerve conducts the impulses to the olfactory cortex of thebrain.

Taste Buds and the Sense of Taste

The word taste comes from the Latin word taxare, which means “to touch, estimate, or judge”.

- Taste buds. The taste buds, or specific receptors for the sense of taste, are widely scattered in the oral cavity; of the 10, 000 or so taste buds we have, most are on the tongue.

- Papillae. The dorsal tongue surface is covered with small peg-like projections, or papillae.

- Circumvallate and fungiform papillae. The taste buds are found on the sides of the large round circumvallate papillae and on the tops of the more numerous fungiform papillae.

- Gustatory cells. The specific cells that respond to chemicals dissolved in the saliva are epithelial cells called gustatory cells.

- Gustatory hairs. Their long microvilli- the gustatory hairs- protrude through the taste pore, and when they are stimulated, they depolarize and impulses are transmitted to thebrain.

- Facial nerve. The facial nerve (VII) serves the anterior part of the tongue.

- Glossopharyngeal and vagus nerves. The other two cranial nerves– the glossopharyngeal and vagus- serve the other taste bud-containing areas.

- Basal cells. Taste bud cells are among the most dynamic cells in the body, and they are replaced every seven to ten days by basal cells found in the deeper regions of the taste buds.

Physiology of the Special Senses

The processes that makes our special senses work include the following:

Pathway of Light through the Eye and Light Refraction

When light passes from one substance to another substance that has a different density, its speed changes and its rays are bent, or refracted.

- Refraction. The refractive, or bending, power of the cornea and humors is constant; however, that of the lens can be changed by changing its shape- that is, by making it more or less convex, so that light can be properly focused on the retina.

- Lens. The greater the lens convexity, or bulge, the more it bends the light; the flatter the lens, the less it bends the light.

- Resting eye. The resting eye is “set” for distant vision; in general, light from a distance source approaches the eye as parallel rays and the lens does not need to change shape to focus properly on the retina.

- Light divergence. Light from a close object tends to scatter and to diverge, or spread out, and the lens must bulge more to make close vision possible; to achieve this, the ciliary body contracts allowing the lens to become more convex.

- Accommodation. The ability of the eye to focus specifically for close objects (those less than 20 feet away) is called accommodation.

- Real image. The image formed on the retina as a result of the light-bending activity of the lens is a real image- that is, it is reversed from left to right, upside down, and smaller than the object.

Visual Fields and Visual Pathways to the Brain

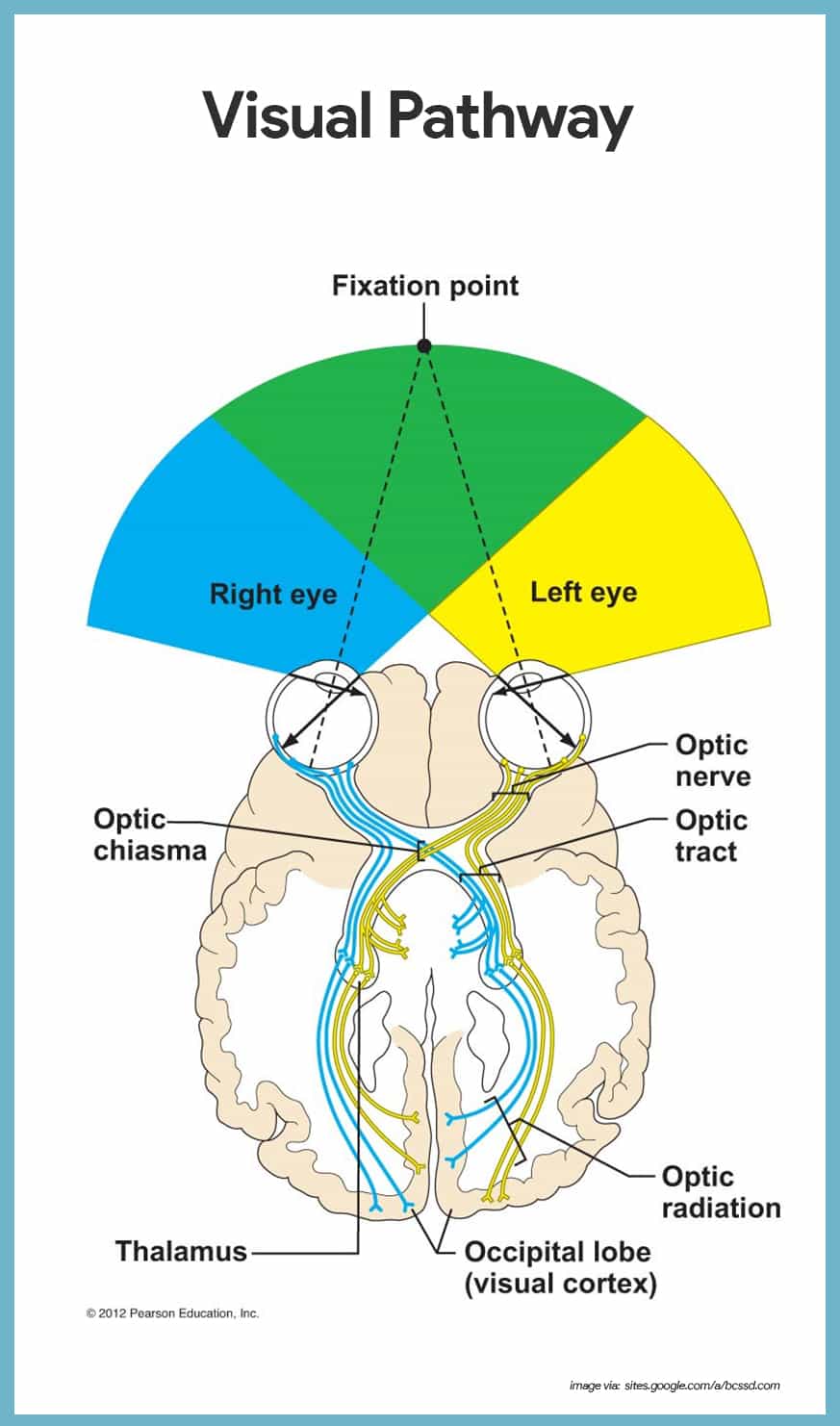

Axons carrying impulses from the retina are bundled together at the posterior aspect of the eyeball and issue from the back of the eye as the optic nerve.

- Optic chiasma. At the optic chiasma, the fibers from the medial side of each eye cross over to the opposite side of the brain.

- Optic tracts. The fiber tracts that result are the optic tracts; each optic tract contains fibers from the lateral side of the eye on the same side and the medial side of the opposite eye.

- Optic radiation. The optic tract fibers synapse with neurons in the thalamus, whose axons form the optic radiation, which runs to the occipital lobe of the brain; there they synapse with the cortical cells, and visual interpretation, or seeing, occurs.

- Visual input. Each side of the brain receives visual input from both eyes-from the lateral field of vision of the eye on its own side and from the medial field of the other eye.

- Visual fields. Each eye “sees” a slightly different view, but their visual fields overlap quite a bit; as a result of these two facts, humans have binocular vision, literally “two-eyed vision” provides for depth perception, also called “three-dimensional vision” as our visual cortex fuses the two slightly different images delivered by the two eyes.

Mechanisms of Equilibrium

The equilibrium receptors of the inner ear, collectively called the vestibular apparatus, can be divided into two functional arms- one arm responsible for monitoring static equilibrium and the other involved with dynamic equilibrium.

Static Equilibrium

Within the membrane sacs of the vestibule are receptors called maculae that are essential to our sense of static equilibrium.

- Maculae. The maculae report on changes in the position of the head in space with respect to the pull of gravity when the body is not moving.

- Otolithic hair membrane. Each macula is a patch of receptor (hair) cells with their “hairs” embedded in the otolithic hair membrane, a jelly-like mass studded with otoliths, tiny stones made of calcium salts.

- Otoliths. As the head moves, the otoliths roll in response to changes in the pull of gravity; this movement creates a pull on the gel, which in turn slides like a greased plate over the hair cells, bending their hairs.

- Vestibular nerve. This event activates the hair cells, which send impulses along the vestibular nerve (a division of cranial nerve VIII) to the cerebellum of the brain, informing it of the position of the head in space.

- Vibrations. To excite the hair cells in the organ of Corti in the inner ear, sound wave vibrations must pass through air, membranes, bone and fluid.

- Sound transmission. The cochlea is drawn as though it were uncoiled to make the events of sound transmission occurring there easier to follow.

- Low frequency sound waves. Sound waves of low frequency that are below the level of hearing travel entirely around the cochlear duct without exciting hair cells.

- High frequency sound waves. But sounds of higher frequency result in pressure waves that penetrate through the cochlear duct and basilar membrane to reach the scala tympani; this causes the basilar membrane to vibrate maximally in certain areas in response to certain frequencies of sound, stimulating particular hair cells and sensoryneurons.

- Length of fibers. The length of the fibers spanning the basilar membrane tune specific regions to vibrate at specific frequencies; the higher notes- 20, 000 Hertz (Hz)- are detected by shorter hair cells along the base of the basilar membrane.

- Crista ampullaris. Within the ampulla, a swollen region at the base of each membranous semicircular canal is a receptor region called crista ampullaris, or simply crista, which consists of a tuft of hair cells covered with a gelatinous cap called the cupula.

- Head movements. When the head moves in an arclike or angular direction, the endolymph in the canal lags behind.

- Bending of the cupula. Then, as the cupula drags against the stationary endolymph, the cupula bends- like a swinging door- with the body’s motion.

- Vestibular nerve. This stimulates the hair cells, and impulses are transmitted up the vestibular nerve to the cerebellum.

- Semicircular canals. The semicircular canals are oriented in the three planes of space; thus regardless of which plane one moves in, there will be receptors to detect the movement.

- Crista ampullaris. Within the ampulla, a swollen region at the base of each membranous semicircular canal is a receptor region called crista ampullaris, or simply crista, which consists of a tuft of hair cells covered with a gelatinous cap called the cupula.

- Head movements. When the head moves in an arclike or angular direction, the endolymph in the canal lags behind.

- Bending of the cupula. Then, as the cupula drags against the stationary endolymph, the cupula bends- like a swinging door- with the body’s motion.

- Vestibular nerve. This stimulates the hair cells, and impulses are transmitted up the vestibular nerve to the cerebellum.

Mechanism of Hearing

The following is the route of sound waves through the ear and activation of the cochlear hair cells.

- Vibrations. To excite the hair cells in the organ of Corti in the inner ear, sound wave vibrations must pass through air, membranes, bone and fluid.

- Sound transmission. The cochlea is drawn as though it were uncoiled to make the events of sound transmission occurring there easier to follow.

- Low frequency sound waves. Sound waves of low frequency that are below the level of hearing travel entirely around the cochlear duct without exciting hair cells.

- High frequency sound waves. But sounds of higher frequency result in pressure waves that penetrate through the cochlear duct and basilar membrane to reach the scala tympani; this causes the basilar membrane to vibrate maximally in certain areas in response to certain frequencies of sound, stimulating particular hair cells and sensoryneurons.

- Length of fibers. The length of the fibers spanning the basilar membrane tune specific regions to vibrate at specific frequencies; the higher notes- 20, 000 Hertz (Hz)- are detected by shorter hair cells along the base of the basilar membrane.

Comments

Post a Comment